I recently tackled the Water Treatment reverse engineering challenge from the CyberSCI Regionals 2025-26. The challenge involves a legacy 16-bit MS-DOS executable (wt.exe) and consists of three flags.

I managed to solve the first flag during the hackathon and the second one afterwards. This post details how I cracked the password to get access to the menu page.

Here is how I went from raw assembly to a successful crack using Ghidra and Python.

Initial Reconnaissance

Before diving into Ghidra, I started with some basic file analysis. I used the file command to check the file type and metadata:

$ file wt.exe

wt.exe: MS-DOS executable, MZ for MS-DOS

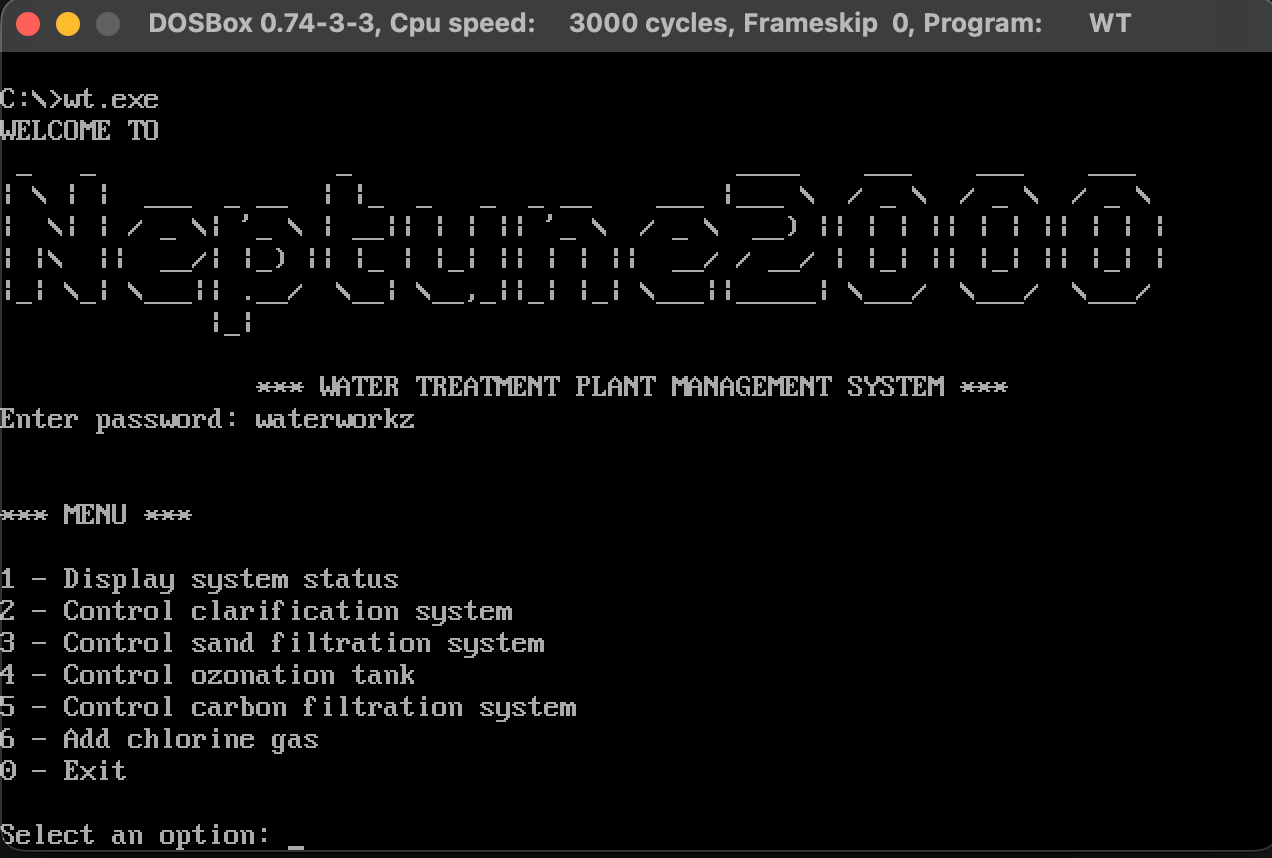

This confirmed it was a legacy 16-bit MS-DOS executable. To run it, I installed DOSBox. When I ran the executable in DOSBox, it displayed the system name Neptune2000 (Flag 1) and then prompted: “Enter password: “.

After this initial check, I loaded the binary into Ghidra and ran the auto-analysis (making sure to select the 16-bit x86 Real Mode processor). I started by looking for “low hanging fruit”—strings.

Opening the Defined Strings window, I found a string:

13dc:0073: "Enter password: "

So I decided to find where this string is referenced and which function handles the comparison between the password and the user input.

One hurdle here is 16-bit DOS segmentation. Memory is addressed with segment:offset, where each segment is a contiguous 64 KB window. Ghidra can recover a lot, but it doesn’t always automatically connect data in one segment to code in another, so I had to manually follow these references.

After searching, this is where the string was referenced inside FUN_1000_01ee():

1000:01fc b8 73 00 MOV AX

Analyzing the Logic

The authentication logic in FUN_1000_01ee was relatively straightforward once the noise was filtered out. Here is the breakdown of the assembly flow:

1000:01fc MOV AX, DAT_13dc_0073 ; Load "Enter password" string

1000:01ff CALL FUN_print_string ; Print it

1000:0210 CALL FUN_1000_0010 ; <--- Interesting Function A

1000:0213 MOV BX, 0x10 ; Length = 16 bytes

1000:0216 MOV DX, 0x644 ; Load Target Address

1000:0219 LEA AX, [BP + -0x10] ; Load User Input Buffer

1000:021c CALL FUN_memcmp ; <--- Interesting Function B

The Comparison

The function ending at 021c (FUN_memcmp) takes the user input and compares it against 16 bytes stored at 0x644. Naturally, I checked the memory at 0x644.

13dc:0644 9e ?? 9Eh

13dc:0645 46 ?? 46h F

13dc:0646 24 ?? 24h $

13dc:0647 8d ?? 8Dh

13dc:0648 91 ?? 91h

13dc:0649 fd ?? FDh

13dc:064a cb ?? CBh

13dc:064b ec ?? ECh

13dc:064c b3 ?? B3h

13dc:064d f4 ?? F4h

13dc:064e ba ?? BAh

13dc:064f 7c ?? 7Ch |

13dc:0650 aa ?? AAh

13dc:0651 e3 ?? E3h

13dc:0652 8b ?? 8Bh

13dc:0653 0d ?? 0Dh

These bytes are not ASCII characters. This confirms that the program isn’t comparing our input against a plain-text password. It is hashing (or encrypting) our input first, then comparing the result.

This means FUN_1000_0010 (called right before the comparison) is our hashing function.

Identifying the Algorithm

I dove into FUN_1000_0010 to understand how the input was being transformed. The decompiled C code looked messy, but two specific patterns stood out.

The S-Box

The code heavily referenced a lookup table at address 0x43a. I inspected this memory region:

13dc:043a 29 2E 43 C9 A2 D8 7C 01 ...

A Google search for this byte prefix revealed it matches the MD2 S-table (derived from the digits of Pi). That lookup table is a strong signature for the MD2 (Message Digest 2) algorithm.

The Checksum Loop

Further confirming this, I found a loop in the decompilation that matched the MD2 checksum update pattern (a rolling byte L over 16-byte blocks). In MD2, this update looks like C[i] = C[i] XOR S[M[i] XOR L] followed by L = C[i].

// Ghidra Decompilation

*(byte *)((*(byte *)(uVar6 + iVar4 + iStack_e) ^ bStack_a) + 0x43a);

0x43ais the S-Box.- The

^operator is the XOR. - The loop structure was iterating over a 16-byte block.

Conclusion: The program hashes the user input using MD2 and compares it to the hardcoded hash at 0x644.

Challenges Encountered

During the analysis, I faced a couple of interesting hurdles:

MS-DOS Segmentation & Ghidra

MS-DOS executables use segmentation for memory layouts, and Ghidra doesn’t always infer segment assumptions the way you’d expect. I had to manually follow segment:offset pairs to confirm where data was being read from.

Recognizing the Hash Function

I am not familiar with legacy hash functions, so I didn’t recognize the algorithm during the hackathon. The S-Box looked like random data at first. It wasn’t until I searched for the specific byte sequence that I realized it was MD2.

The Solution

Since MD2 is a one-way hash function, I couldn’t just decrypt the target bytes. However, MD2 is an obsolete algorithm (from 1989), and the password was likely simple. This made it a perfect candidate for a dictionary attack.

This is a Python script using pycryptodome to hash passwords from the rockyou.txt wordlist and compare them to our target.

Solver Script

from Crypto.Hash import MD2

# The target hash extracted from 0x644

TARGET = bytes.fromhex("9E 46 24 8D 91 FD CB EC B3 F4 BA 7C AA E3 8B 0D")

def main():

print("[*] Brute-forcing MD2 target...")

wordlist_path = "/usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt"

try:

with open(wordlist_path, "r", encoding="latin-1") as f:

for count, line in enumerate(f):

password = line.strip()

# Calculate MD2

h = MD2.new()

h.update(password.encode("latin-1"))

if h.digest() == TARGET:

print(f"\n[!!!] PASSWORD FOUND: {password}")

return

if count % 100000 == 0:

print(f"[*] Checked {count}...", end="\r")

except FileNotFoundError:

print("Error: rockyou.txt not found.")

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Note: Why we use encoding = latin-1 instead of utf-8?

rockyou.txt commonly contains non-UTF-8 bytes; latin-1 is often used here because it can decode any byte value without errors.

Result

I ran the script, and within a few seconds, it hit a match and allows me enter the menu:

[*] Checked 2800000...

[!!!] PASSWORD FOUND: waterworkz

I fired up the executable in DOSBox, typed waterworkz, and bypassed the check!

It turns out that waterworkz is the password, which corresponds to the second flag. The system name (Flag 1) is Neptune2000.

Flag 1 (System Name): Neptune2000

Flag 2 (Password): waterworkz

References

[1] https://blogsystem5.substack.com/p/dos-memory-models

[2] https://handwiki.org/wiki/MD2_(hash_function)#MD2_hashes

[3] https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc1319